Exposing the False Use of ‘Ummiyeen’ in Hadith

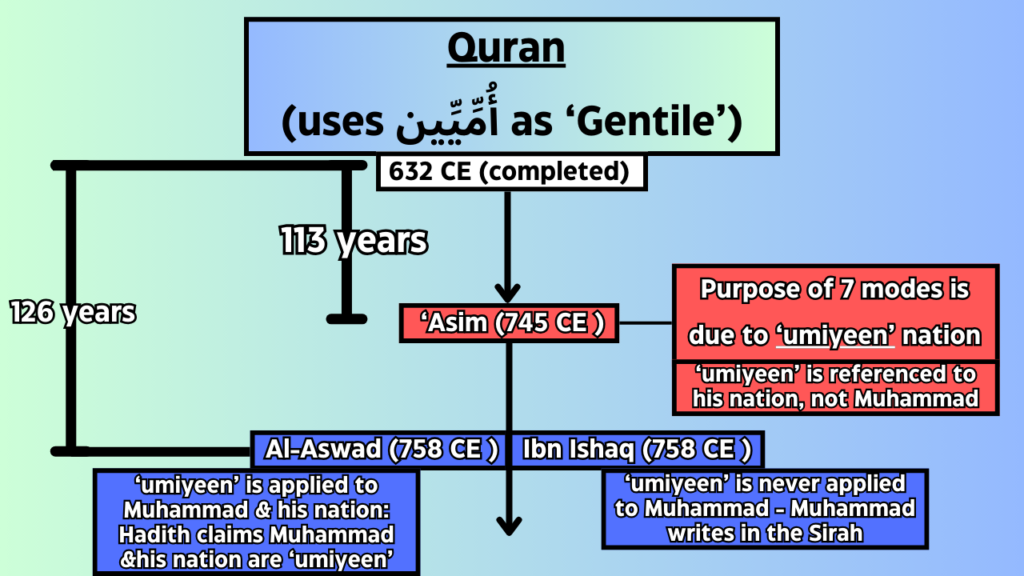

The term “Ummiyeen,” often translated as “illiterate,” has been a subject of significant debate. While traditionally interpreted as a reference to the Prophet Muhammad and his nation’s supposed “lack of literacy,” a closer analysis reveals that “Ummiyeen” more accurately means “gentile,” referring to those outside the scriptural traditions. This understanding aligns seamlessly with the Qur’anic context. The purpose of this blog post, however, is not to prove from the Qur’an that “Ummiyeen” means “gentile” (check out the QT blog linked below for that). Instead, our focus is to expose fabricated hadiths that anachronistically misuse the term, properly date these fabrications to their origins, and trace how this misunderstanding of the term emerged over time.

By tracing the origins of these hadiths to narrators like Asim and Al-Aswad, we uncover a pattern of deliberate or mistaken reinterpretation of “Ummiyeen” to mean “illiterate.” This misinterpretation not only results in incoherent narratives but also betrays historical anachronisms, as evidenced by discrepancies in early biographical works like those of Ibn Ishaq, who never describes the Prophet as illiterate. Furthermore, both Asim and Al-Aswad, prominent narrators from Kufa, appear to be key figures in propagating this flawed notion.

#1 – “We Are An (Ummiyeen) Nation. We Neither Calculate Nor Write…”

Hadith in Question 1:

أحمد:٦٠٤١ – حَدَّثَنَا هَاشِمٌ حَدَّثَنَا إِسْحَاقُ بْنُ سَعِيدٍ عَنْ أَبِيهِ عَنِ ابْنِ عُمَرَ قَالَ قَالَ رَسُولُ اللهِ ﷺ نَحْنُ أُمَّةٌ أُمِّيُّونَ لَا نَحْسُبُ وَلَا نَكْتُبُ الشَّهْرُ هَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَقَبَضَ إِبْهَامَهُ فِي الثَّالِثَةِ

Translation:

Ahmad: 6041 – Hashim said: Ishaq ibn Sa’id said from his father, from Ibn Umar who said: The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said: “We are an illiterate nation. We neither calculate nor write. The month is like this, and like this, and like this,” and he clasped his thumb in the third position.

Source

Narration Text

Additional Details

Status

Ahmad: 6041

حَدَّثَنَا هَاشِمٌ حَدَّثَنَا إِسْحَاقُ بْنُ سَعِيدٍ عَنْ أَبِيهِ عَنِ ابْنِ عُمَرَ قَالَ قَالَ رَسُولُ اللهِ ﷺ نَحْنُ أُمَّةٌ أُمِّيُّونَ لَا نَحْسُبُ وَلَا نَكْتُبُ الشَّهْرُ هَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَقَبَضَ إِبْهَامَهُ فِي الثَّالِثَةِ “We are an unlettered nation. We do not calculate or write down. The month is like this, like this, and like this.” And he held up his thumb, his index finger, and his middle finger.

This narration holds the original phrasing and context with a subtle hand gesture description in the third phase.

Authentic (Ibn Hajar)

Abu Dawood: 2319

حَدَّثَنَا سُلَيْمَانُ بْنُ حَرْبٍ حَدَّثَنَا شُعْبَةُ عَنِْ الأَسْوَدِ بْنِ قَيْسٍ عَنْ سَعِيدِ بْنِ عَمْرٍو يَعْنِي ابْنَ سَعِيدِ بْنِ الْعَاصِ عَنِ ابْنِ عُمَرَ قَالَ قَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ ﷺ إِنَّا أُمَّةٌ أُمِّيَّةٌ لاَ نَكْتُبُ وَلاَ نَحْسُبُ الشَّهْرُ هَكَذَا وَ هَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَخَنَسَ سُلَيْمَانُ أُصْبَعَهُ فِي الثَّالِثَةِ يَعْنِي تِسْعًا وَعِشْرِينَ وَثَلاَثِينَ “We are an illiterate nation, we do not write or calculate. The month is like this, and like this, and like this.” And Sulayman bent his finger, referring to 29 and 30.

The gesture is slightly different, referring to 29 and 30 days.

Authentic (Al-Albani)

Ahmad: 5017

حَدَّثَنَا مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ جَعْفَرٍ حَدَّثَنَا شُعْبَةُ عَنِْ الأَسْوَدِ بْنِ قَيْسٍ سَمِعْتُ سَعِيدَ بْنَ عَمْرِو بْنِ سَعِيدٍ يُحَدِّثُ أَنَّهُ سَمِعَ ابْنَ عُمَرَ يُحَدِّثُ عَنِ النَّبِيِّ ﷺ أَنَّهُ قَالَ إِنَّا أُمَّةٌ أُمِّيَّةٌ لَا نَكْتُبُ وَلاَ نَحْسُبُ الشَّهْرُ هَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَعَقَدَ الْإِبْهَامَ فِي الثَّالِثَةِ وَالشَّهْرُ هَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا يَعْنِي تَمَامَ ثَلَاثِينَ “We are an unlettered nation, we do not write or calculate. The month is like this, like this, and like this,” and he held up his thumb in the third phase, indicating the completion of 30 days.

It focuses on the idea of completing 30 days, different from Ahmad 6041’s focus on 29 and 30 as variable months.

Authentic (Arnaout)

Muslim: 1080n

حَدَّثَنَا أَبُو بَكْرِ بْنُ أَبِي شَيْبَةَ حَدَّثَنَا غُنْدَرٌ عَنْ شُعْبَةَ ح وَحَدَّثَنَا مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ الْمُثَنَّى وَابْنُ بَشَّارٍ قَالَ ابْنُ الْمُثَنَّى حَدَّثَنَا مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ جَعْفَرٍ حَدَّثَنَا شُعْبَةُ عَنِ الأَسْوَدِ بْنِ قَيْسٍ قَالَ سَمِعْتُ سَعِيدَ بْنَ عَمْرِو بْنِ سَعِيدٍ أَنَّهُ سَمِعَ ابْنَ عُمَرَ ؓ يُحَدِّثُ عَنِ النَّبِيِّ ﷺ قَالَ إِنَّا أُمَّةٌ أُمِّيَّةٌ لاَ نَكْتُبُ وَلاَ نَحْسُبُ الشَّهْرُ هَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَعَقَدَ الإِبْهَامَ فِي الثَّالِثَةِ “We are an illiterate nation, we do not write or calculate. The month is like this, and like this, and like this,” and he held up his thumb in the third phase, indicating 30 days.

Same as Ahmad 5017, with focus on 30 days in a month.

Authentic (Muslim)

Al-Bayhaqi: 13287

وَأَخْبَرَنَا أَبُو نَصْرٍ مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ أَحْمَدَ بْنِ إِسْمَاعِيلَ الطَّابَرَانِيُّ بِهَا ثنا أَبُو مُحَمَّدٍ عَبْدُ اللهِ بْنُ أَحْمَدَ بْنِ مَنْصُورٍ الطُّوسِيُّ ثنا مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ إِسْمَاعِيلَ الصَّائِغُ ثنا رَوْحُ بْنُ عُبَادَةَ ثنا شُعْبَةُ قَالَ سَمِعْتُ الْأَسْوَدَ بْنِ قَيْسٍ عَنْ سَعِيدِ بْنِ عَمْرِو بْنِ سَعِيدٍ عَنِ ابْنِ عُمَرَ ؓ عَنِ النَّبِيِّ ﷺ قَالَ إِنَّا أُمَّةٌ أُمِّيَّةٌ لَا نَكْتُبُ وَلَا نَحْسُبُ وَالشَّهْرُ هَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَقَبَضَ إِصْبَعَهُ وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا يَعْنِي ثَلَاثِينَ “We are an illiterate nation, we do not write or calculate. The month is like this, and like this, and like this.” He held up his finger for the completion of the month, referring to 30 days.

No difference in wording or gesture from Ahmad 6041.

Authentic (Bayhaqi)

Al-Bayhaqi: 8200

أَخْبَرَنَا أَبُو عَبْدِ اللهِ الْحَافِظُ أَخْبَرَنِي عَبْدُ الرَّحْمَنِ بْنُ الْحَسَنِ الْقَاضِي ثنا إِبْرَاهِيمُ بْنُ الْحُسَيْنِ ثنا آدَمُ ثنا شُعْبَةُ ثنا الْأَسْوَدُ بْنِ قَيْسٍ قَالَ سَمِعْتُ سَعِيدَ بْنَ عُمَرٍو يَقُولُ سَمِعْتُ عَبْدَ اللهِ بْنَ عُمَرَ يَقُولُ قَالَ رَسُولُ اللهِ ﷺ إِنَّا أُمَّةٌ أُمِّيَّةٌ لَا نَكْتُبُ وَلاَ نَحْسِبُ الشَّهْرُ هَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا يَعْنِي ثَلَاثِينَ ثُمَّ قَالَ وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَضَمَّ إِبْهَامَهُ يَعْنِي تِسْعًا وَعِشْرِينَ “We are an illiterate nation, we do not calculate or write. The month is like this, like this, and like this, meaning 30.” Then he said, “Like this, like this, and like this,” and held up his thumb for 29 days.

The hadith mentions both 30 and 29 days in rotation.

Authentic (Bayhaqi)

Ahmad: 6129

حَدَّثَنَا عَبِيدَةُ بْنُ حُمَيْدٍ حَدَّثَنِي الْأَسْوَدُ بْنُ قَيْسٍ عَنْ سَعِيدِ بْنِ عَمٍرو الْقُرَشِيِّ أَنَّ عَبْدَ اللهِ بْنَ عُمَرَ حَدَّثَهُمْ عَنِ النَّبِيِّ ﷺ أَنَّهُ قَالَ إِنَّا أُمَّةٌ أُمِّيَّةٌ لَا نَكْتُبُ وَلَا نَحْسُبُ وَإِنَّ الشَّهْرَ هَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا ثُمَّ نَقَصَ وَاحِدَةً فِي الثَّالِثَةِ “We are an illiterate nation, we do not calculate or write. The month is like this, like this, and like this,” and he made one reduction in the third phase.

This narration emphasizes a decrement, slightly altering the gesture in terms of how the third finger is used.

Authentic (Ibn Hajar)

Al-Kubra al-Nasa’i: 2461

حَدَّثَنَا مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ الْمُثَنَّى وَمُحَمَّدُ بْنُ بَشَّارٍ عَنْ مُحَمَّدٍ عَنْ شُعْبَةَ عَنِ الْأَسْوَدِ بْنِ قَيْسٍ قَالَ سَمِعْتُ سَعِيدَ بْنَ عَمْرِو بْنِ سَعِيدِ بْنِ الْعَاصِ أَنَّهُ سَمِعْتُ ابْنَ عُمَرَ يُحَدِّثُ عَنِ النَّبِيِّ ﷺ قَالَ «إِنَّا أُمَّةٌ أُمِّيَّةٌ لَا نَحْسُبُ وَلَا نَكْتُبُ وَالشَّهْرُ هَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا» وَعَقَدَ الْإِبْهَامَ فِي الثَّالِثَةِ “We are an illiterate nation, we do not calculate or write. The month is like this, and like this, and like this.” And he held up his thumb in the third phase.

Similar to Ahmad 6041, with a direct reference to the thumb being held up in the third phase.

Authentic (Nasa’i)

Ahmad: 5137

حَدَّثَنَا هُشَيْمٌ حَدَّثَنَا عُمَرُ بْنُ مُحَمَّدٍ عَنْ سَعِيدِ بْنِ جُبَيْرٍ عَنْ عَبْدِ اللَّـهِ بْنِ عُمَرَ قَالَ قَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّـهِ ﷺ إِنَّا أُمَّةٌ أُمِّيَّةٌ لَا نَكْتُبُ وَلاَ نَحْسُبُ الشَّهْرُ هَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَعَقَدَ الإِبْهَامَ فِي الثَّالِثَةِ “We are an illiterate nation, we do not write or calculate. The month is like this, and like this, and like this.” And he held up his thumb in the third phase.

The wording remains the same as Ahmad 6041, but there is a slight variation in the narrator chain, mentioning a different isnad.

Authentic (Ahmad)

Nasa’i: 2140

أَخْبَرَنَا مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ الْمُثَنَّى قَالَ حَدَّثَنَا عَبْدُ الرَّحْمَنِ عَنْ سُفْيَانَ عَنِ الأَسْوَدِ بْنِ قَيْسٍ عَنْ سَعِيدِ بْنِ عَمْرٍو عَنِ ابْنِ عُمَرَ عَنِ النَّبِيِّ ﷺ قَالَ إِنَّا أُمَّةٌ أُمِّيَّةٌ لاَ نَحْسُبُ وَلاَ نَكْتُبُ الشَّهْرُ هَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا “We are an unlettered nation, we do not write or calculate. The month is like this, like this, and like this,” mentioning 29 days.

Focus on 29 days in one of the rotations.

Authentic (Ali Zay’i)

Nasa’i: 2141

أَخْبَرَنَا مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ الْمُثَنَّى وَمُحَمَّدُ بْنُ بَشَّارٍ عَنْ مُحَمَّدٍ عَنْ شُعْبَةَ عَنِ الأَسْوَدِ بْنِ قَيْسٍ قَالَ سَمِعْتُ سَعِيدَ بْنَ عَمْرِو بْنِ سَعِيدِ بْنِ الْعَاصِ أَنَّهُ سَمِعَ ابْنَ عُمَرَ يُحَدِّثُ عَنِ النَّبِيِّ ﷺ قَالَ إِنَّا أُمَّةٌ أُمِّيَّةٌ لاَ نَحْسُبُ وَلَا نَكْتُبُ وَالشَّهْرُ هَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا “We are an illiterate nation, we do not calculate or write. The month is like this, and like this, and like this.” He held up his finger indicating 30 days.

Similar in content to Ahmad 6041, but with slight changes in phrasing.

Authentic (Nasa’i)

Al-Kubra al-Nasa’i: 2462

أَخْبَرَنَا مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ الْمُثَنَّى وَمُحَمَّدُ بْنُ بَشَّارٍ عَنْ مُحَمَّدٍ عَنْ شُعْبَةَ عَنِ الْأَسْوَدِ بْنِ قَيْسٍ قَالَ سَمِعْتُ سَعِيدَ بْنَ عَمْرِو بْنِ سَعِيدِ بْنِ الْعَاصِ أَنَّهُ سَمِعْتُ ابْنَ عُمَرَ يُحَدِّثُ عَنِ النَّبِيِّ ﷺ قَالَ «إِنَّا أُمَّةٌ أُمِّيَّةٌ لَا نَحْسُبُ وَلَا نَكْتُبُ وَالشَّهْرُ هَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا» وَعَقَدَ الْإِبْهَامَ فِي الثَّالِثَةِ “We are an illiterate nation, we do not calculate or write. The month is like this, and like this, and like this.” with the thumb held up for the third finger, indicating 30 days.

Same as Ahmad 6041 with a small change in phrasing.

Authentic (Nasa’i)

Al-Kubra al-Nasa’i: 5853

حَدَّثَنَا أَبُو سَعِيدٍ عَبْدُ الرَّحْمَنِ بْنُ نَجْدَةَ حَدَّثَنَا أَبُو النَّضْرِ حَدَّثَنَا شُعْبَةُ عَنْ الأَسْوَدِ بْنِ قَيْسٍ عَنْ سَعِيدِ بْنِ عَمْرٍو عَنْ عَبْدِ اللَّـهِ بْنِ عُمَرَ قَالَ قَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّـهِ ﷺ إِنَّا أُمَّةٌ أُمِّيَّةٌ لَا نَحْسُبُ وَلَا نَكْتُبُ وَالشَّهْرُ هَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا وَهَكَذَا “We are an illiterate nation, we do not calculate or write. The month is like this, and like this, and like this.”

This narration is almost identical to Ahmad 6041, except for the variation in narrator names and slight changes in the phrasing. There is no mention of holding the thumb in the third phase.

No Specific Judgment (N/A)

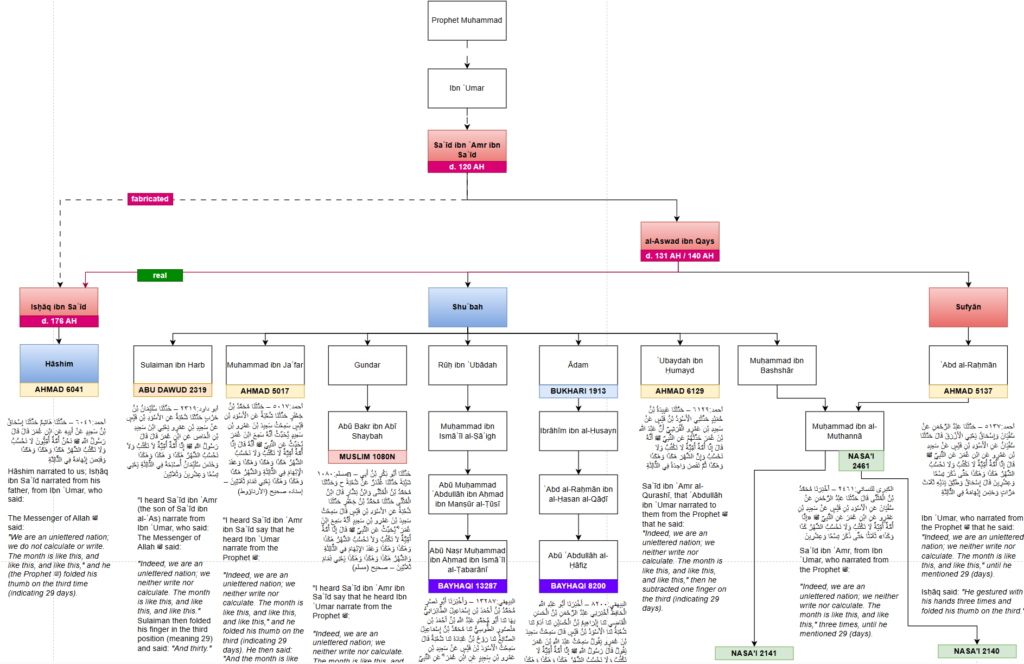

The reliability of hadith transmission is built upon the integrity of the isnad (chain of narrators), which ensures the authenticity of the tradition. However, the practice of tadlees, where a narrator conceals or alters the true source of the narration, can undermine this system of transmission. This study investigates the possibility that Ishaq ibn Sa’id, a second-generation narrator, utilized tadlees to connect a hadith to his father, Sa’id ibn Amr, even though the father was likely deceased by the time Ishaq could have legitimately received traditions from him.

The hadith in question appears to be transmitted from Sa’id ibn Amr, yet there are compelling reasons to suggest that Ishaq ibn Sa’id could not have directly heard it from his father, due to both the death dates involved and the broader historical context. Instead, this argument asserts that Ishaq may have received the hadith from al-Aswad ibn Qays, a key figure in the transmission of this tradition.

The narrators involved in the transmission of this hadith include:

Ishaq ibn Sa’id: A prominent narrator in the early generations of Islamic scholarship, who died around 170 AH (or 176 AH, depending on sources). He is believed to be the son of Sa’id ibn Amr.

Sa’id ibn Amr: A Kufan scholar and narrator, known for transmitting hadith from various sources, who passed away around 120 AH.

Al-Aswad ibn Qays: A key figure in the Kufan hadith transmission, with an unclear death date between 131 AH and 140 AH, known to have allegedly narrate from prominent sources, including Ibn Umar.

The Problem of Death Dates and Transmission:

Ishaq ibn Sa’id’s birth year is somewhat uncertain, but the general consensus is that he was born around 120 AH or earlier. Given that his father, Sa’id ibn Amr, died in 120 AH, it is improbable that Ishaq could have directly heard from him. Even if Ishaq were born right before or after his father’s death, the lack of direct interaction due to his youth and the passing of Sa’id ibn Amr raises serious doubts about this direct transmission.

This discrepancy between the death year of Sa’id ibn Amr and the birth year of Ishaq ibn Sa’id leads to the conclusion that Ishaq could not have personally heard the hadith from his father, unless he was still an infant at the time of his father’s passing, which again complicates the possibility of direct transmission.

On the other hand, al-Aswad ibn Qays was very much alive during Ishaq’s life and could have plausibly been a source of the hadith. Al-Aswad, active in the transmission of hadith in Kufa, would have had ample opportunity to narrate this tradition to Ishaq at a later stage in Ishaq’s life.

Geographic and Temporal Context of Transmission:

Ishaq ibn Sa’id and al-Aswad ibn Qays were both part of the Kufa-based hadith network, and it is highly plausible that Ishaq, who was based in Kufa and had access to the renowned Kufan scholars, could have heard this hadith from al-Aswad ibn Qays.

The fact that al-Aswad ibn Qays was involved in transmitting hadith to figures like Shu’ba and Sufyan al-Thawri, both of whom were critical in shaping early Islamic scholarship, strengthens the argument that Ishaq may have received the hadith from him instead of from his father, Sa’id ibn Amr.

Al-Aswad’s connection to both Kufa and Ibn Umar provides further links to suggest that Ishaq could have heard the tradition from him directly or through intermediaries, particularly since Ishaq was known to be active in Kufa and had a robust network of connections there.

The Role of Tadlees in the Isnad:

Given that Ishaq ibn Sa’id is known to have been a scholar who worked with hadith, it is possible that he engaged in tadlees to connect the hadith to his father, possibly out of a desire to elevate his own chain or to authenticate the tradition. This practice of linking a narration to an earlier, authoritative figure was not uncommon in the early generations.

Tadlees is a complex issue in early hadith transmission, and it often involved narrators transmitting from figures they had never directly met, either by altering the chain or by omitting intermediate narrators. In the case of Ishaq ibn Sa’id, the fact that he did not directly receive the hadith from his father, but rather from al-Aswad ibn Qays, could suggest that he intentionally altered the chain to include his father as a narrator. This is not an uncommon practice in early hadith scholarship, where the reputation of a father could elevate the status of the son’s narration.

Al-Aswad ibn Qays was an established figure in the Kufan hadith community, and it would not be out of character for Ishaq to have received this hadith through him but later fabricated a link to his father, Sa’id ibn Amr, to add authenticity to the transmission.

The argument presented here suggests that Ishaq ibn Sa’id likely did not receive the hadith directly from his father, Sa’id ibn Amr, as the death dates and the geographical limitations between the two individuals make this highly improbable. Instead, it is much more plausible that Ishaq, like many other early narrators, heard the tradition from al-Aswad ibn Qays, who was an active transmitter of hadith in Kufa at the time.

Given the historical and geographical context, and considering the role of tadlees in early hadith transmission, it is likely that Ishaq altered the isnad, fabricating a connection to his father in order to elevate the hadith’s authenticity. Al-Aswad ibn Qays stands out as the more likely source of this narration, and his role as the true link in the isnad deserves closer scrutiny, as it could shed light on broader issues of transmission integrity in early Islamic scholarship. By understanding the dynamics of hadith transmission, particularly the role of tadlees and the reliance on intermediaries, this study contributes to a deeper appreciation of the complexities surrounding early Islamic scholarship and hadith literature. The earliest we can say this hadith goes back to would then be: al-Aswad ibn Qays.

On top of this, Dr. Ahmad Al-Jallad accounts that the pre-islamic ‘days of ignorance’ were not as illiterate as the textual sources claim:

“The old myth that in the pre-Islamic times, the Jahiliyyah were looking at illiterate hordes who had nothing but an oral culture. But indeed, these nomads left us tens of thousands of texts, tens of thousands. Tremendous literacy.“

https://twitter.com/talkquran/status/1872417029661368366

The idea that the Prophet was sent to an “illiterate nation” based on the term “أُمِّيّون” (ummiyoon) in the hadith relies on a common misunderstanding of the term, which is often mistakenly translated as “illiterate.” The term “أُمِّيّون” actually refers to “gentiles” or “non-scriptural,” specifically distinguishing the unscriptured from the scriptured, who had established sacred texts. This distinction is important.

If we attempt to understand this hadith using the correct translation of “أُمِّيّون” as “gentile” rather than “illiterate,” we encounter a significant problem: the hadith would become incoherent. If the Prophet were sent to a “gentile nation,” the meaning of the hadith would no longer align with the rest of the message. For instance, the mention of the Prophet being sent to a nation that is unable to count or track the months (“لَا نَحْسُبُ وَلَا نَكْتُبُ”) would no longer make sense in the context of gentiles, as gentile nations could be literate or numerate. The narrative of the hadith falls apart, because there is no logical reason why a “gentile” nation would be incapable of performing basic administrative tasks like tracking months or counting.

This shows that the hadith, when understood in its original Arabic context, was likely fabricating the idea of an “illiterate” nation. The fabricator of this hadith, al-Aswad ibn Qays, most likely misunderstood the term “أُمِّيّون” as meaning “illiterate” rather than “gentile.” This misinterpretation allowed him to craft a hadith that portrayed the Prophet as being sent to an “illiterate” nation. This distortion of the term, therefore, underpins the fabrication of the hadith, as it relies on a false understanding of the word “أُمِّيّون.” Thus, understanding the term “أُمِّيّون” as “gentiles” exposes the incoherence of the hadith.

Hadith #2 – “O, Gabriel, I Have Been Sent To An (Ummiyeen) Nation…”

Hadith in Question 2:

أحمد:٢٣٤٤٧ – حَدَّثَنَا عَبْدُ الصَّمَدِ حَدَّثَنَا حَمَّادٌ عَنْ عَاصِمٍ عَنْ زِرٍّ عَنْ حُذَيْفَةَ أَنَّ جِبْرِيلَ لَقِيَ رَسُولَ اللهِ ﷺ عِنْدَ حِجَارَةِ الْمِرَاءِ فَقَالَ يَا جِبْرِيلُ إِنِّي أُرْسِلْتُ إِلَى أُمَّةٍ أُمِّيَّةٍ إِلَى الشَّيْخِ وَالْعَجُوزِ وَالْغُلَامِ وَالْجَارِيَةِ وَالشَّيْخِ الَّذِي لَمْ يَقْرَأْ كِتَابًا قَطُّ فَقَالَ إِنَّ الْقُرْآنَ أُنْزِلَ عَلَى سَبْعَةِ أَحْرُفٍ

Translation:

Ahmad: 23447 – Abdu al-Samad narrated to us, Hamad narrated to us from Asim, from Zir, from Hudhayfah, who said: Gabriel met the Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) near the stone of the quarrel and said: “O Gabriel, I have been sent to an illiterate nation, to the old man, the woman, the boy, and the girl, and to the old man who has never read a book.” Gabriel replied: “The Qur’an was revealed in seven modes.“

Reference

Arabic Text

Translation

Matn Difference

Closer Narration

Tirmidhi 2944

لَقِيَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ ﷺ جِبْرِيلَ فَقَالَ يَا جِبْرِيلُ إِنِّي بُعِثْتُ إِلَى أُمَّةٍ أُمِّيِّينَ مِنْهُمُ الْعَجُوزُ وَالشَّيْخُ الْكَبِيرُ وَالْغُلاَمُ وَالْجَارِيَةُ وَالرَّجُلُ الَّذِي لَمْ يَقْرَأْ كِتَابًا قَطُّ قَالَ يَا مُحَمَّدُ إِنَّ الْقُرْآنَ أُنْزِلَ عَلَى سَبْعَةِ أَحْرُفٍ

The Messenger of Allah ﷺ met Jibril and said, “O Jibril, I have been sent to an unlettered nation, among them the elderly woman, the elderly man, the youth, and the maid, and the one who has never read a book.” Jibril replied, “O Muhammad, the Qur’an was revealed in seven modes.”

– Additional Mention: “The elderly woman” and “the elderly man” are mentioned. – Added Detail: “The one who has never read a book.” – Reference to Jibril’s reply: “O Muhammad…”

Closest to Ibn Hibban (739) and Ahmad (21204), both mention specific individuals and give a detailed account.

Ibn Hibban 739

لَقِيَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ ﷺ جِبْرِيلَ ﷺ فَقَالَ لَهُ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ ﷺ «إِنِّي بُعِثْتُ إِلَى أُمَّةٍ أُمَيَّةٍ مِنْهُمُ الْغُلَامُ وَالْجَارِيَةُ وَالْعَجُوزُ وَالشَّيْخُ الْفَانِي» قَالَ «مُرْهُمْ فَلْيَقْرَؤُوا الْقُرْآنَ عَلَى سَبْعَةِ أَحْرُفٍ»

The Messenger of Allah ﷺ met Jibril (ﷺ) and said to him, “I have been sent to an unlettered nation, among them are the youth, the maid, the elderly, and the elderly man.” Jibril replied, “Command them to read the Qur’an in seven modes.”

– Simpler Text: The word “venerable” or “old” is not used, instead just “elderly”. – Differences: “the one who has never read a book” is not mentioned.

Closer to Tirmidhi (2944), especially regarding the unlettered nation and mentioning youth, maid, and elderly.

Ahmad 21204

لَقِيَ رَسُولُ اللهِ ﷺ جِبْرِيلُ عِنْدَ أَحْجَارِ الْمِرَاءِ فَقَالَ رَسُولُ اللهِ ﷺ لِجِبْرِيلَ إِنِّي بُعِثْتُ إِلَى أُمَّةٍ أُمِّيِّينَ فِيهِمُ الشَّيْخُ الْعَاسِي وَالْعَجُوزَةُ الْكَبِيرَةُ وَالْغُلَامُ قَالَ فَمُرْهُمْ فَلْيَقْرَؤُوا الْقُرْآنَ عَلَى سَبْعَةِ أَحْرُفٍ

The Messenger of Allah ﷺ met Jibril near the stones of al-Mirā’ and said, “I have been sent to an unlettered nation, among them the rebellious elderly, the old woman, and the youth.” Jibril replied, “Tell them to read the Qur’an in seven modes.”

– Difference in wording: “Rebellious elderly” instead of “elderly.” – Added phrase: “Near the stones of al-Mirā’.”

Closer to Ahmad 23398, sharing a similar phrasing for the elderly.

Ahmad 23447

لَقِيَ رَسُولَ اللهِ ﷺ جِبْرِيلَ عِندَ حِجَارَةِ الْمِرَاءِ فَقَالَ يَا جِبْرِيلُ إِنِّي أُرْسِلْتُ إِلَى أُمَّةٍ أُمِّيَّةٍ إِلَى الشَّيْخِ وَالْعَجُوزِ وَالْغُلَامِ وَالْجَارِيَةِ وَالشَّيْخِ الَّذِي لَمْ يَقْرَأْ كِتَابًا قَطُّ فَقَالَ إِنَّ الْقُرْآنَ أُنْزِلَ عَلَى سَبْعَةِ أَحْرُفٍ

The Messenger of Allah ﷺ met Jibril near the stone of al-Mirā’ and said, “I have been sent to an unlettered nation: the elderly man, the old woman, the youth, the maid, and the one who has never read a book.” Jibril replied, “The Qur’an was revealed in seven modes.”

– Added phrase: “Near the stone of al-Mirā’.” – Difference in phrasing: “The one who has never read a book” is added at the end.

Closer to Ahmad 23398, in terms of the addition about “the one who has never read a book.”

Ahmad 23398

حَدَّثَنَا عَفَّانُ حَدَّثَنَا حَمَّادٌ يَعْنِي ابْنَ سَلَمَةَ عَنْ عَاصِمٍ عَنْ زِرٍّ عَنْ حُذَيْفَةَ أَنَّ رَسُولَ اللَّهِ ﷺ قَالَ لَقِيتُ جِبْرِيلَ عَلَيْهِ السَّلَامُ عِندَ أَحْجَارِ الْمِرَاءِ فَقَالَ يَا جِبْرِيلُ إِنِّي أُرْسِلْتُ إِلَى أُمَّةٍ أُمِّيَّةٍ الرَّجُلُ وَالْمَرْأَةُ وَالْغُلَامُ وَالْجَارِيَةُ وَالشَّيْخُ الْعَاسِي الَّذِي لَمْ يَقْرَأْ كِتَابًا قَطُّ قَالَ إِنَّ الْقُرْآنَ نَزَلَ عَلَى سَبْعَةِ أَحْرُفٍ

The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said, “I met Jibril at the stones of al-Mirā’ and said, ‘O Jibril, I have been sent to an unlettered nation: the man, the woman, the youth, the maid, and the rebellious elderly who has never read a book.’ Jibril replied, ‘The Qur’an was revealed in seven modes.'”

– Difference in phrasing: The phrase “the rebellious elderly” is used. – **Mention of “stones of al-Mirā'” is included.

Closer to Ahmad 23447, shares the specific mention of the “stones of al-Mirā’” and the phrase “the rebellious elderly.”

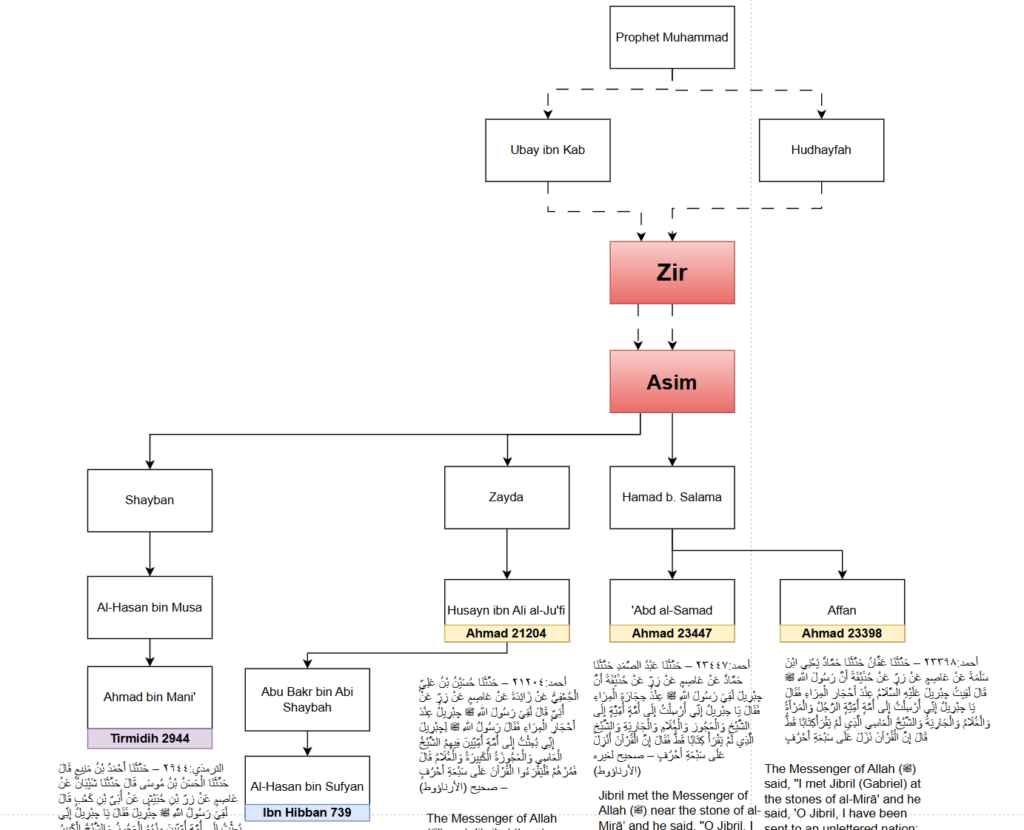

To prove that the hadith about the seven ahruf (modes) was fabricated by Asim ibn Abi Najūd, we must look at several factors, including his personal background, the political climate during his time, the nature of his hadith transmissions, and the context surrounding the seven ahruf tradition.

Asim ibn Abi Najūd was an influential reciter of the Qur’an, especially in Kufa, and one of the seven primary transmitters of Qur’anic recitation. However, his role in hadith transmission was more problematic. Though he was trusted, several scholars, including Ibn Saʿd and Yaʿqūb ibn Sufyān, noted that Asim was prone to errors in his hadith narrations. Specifically, Ibn Saʿd mentioned that while Asim was trustworthy, he made many mistakes in his hadith transmissions.

Ibn Saʿd: He reports that Asim was a “trustworthy” transmitter but also acknowledged that he “made many mistakes in his hadith” (Ikmāl Tahdhīb al-Kamāl, 7/100). This suggests that while Asim was reliable in terms of his Qur’anic recitation, his transmission of hadiths should be approached with caution, especially considering his tendency to make errors.

Yaʿqūb ibn Sufyān: He stated that Asim had “inconsistencies” in his hadith transmissions, again suggesting that Asim was not infallible, and his narrations, particularly when isolated, should be scrutinized (Tahdhīb al-Kamāl, 13/473).

This sets the stage for the possibility that Asim could have fabricated or altered hadiths to suit certain needs.

Analysis of the Hadith Chain and Fabrication

The hadith in question about the seven ahruf contains a chain of transmission that starts with Asim ibn Abi Najūd. Let’s examine the chain and the problems with the transmission:

Chain of Narrators: Ahmad ibn Hanbal reports that the hadith was transmitted by Abdu al-Samad, who narrated from Hamad, who narrated from Asim, from Zir, from Hudhayfah. This chain of transmission is problematic because:

Zir ibn Hubaysh: Zir is not known to have consistently transmitted this specific hadith about the seven ahruf, and his chain with Asim is not corroborated by other reliable sources. The lack of corroborative evidence weakens the claim that this hadith comes from the companions of the Prophet, especially when we consider that other chains of transmission do not report the same content.

Asim’s Role: Asim is the central figure in the transmission, and there is a significant absence of corroborating narrations from other sources to validate his transmission. The fact that Asim is the sole transmitter in this case raises red flags regarding the authenticity of the hadith.

Asim’s Possible Motivations for Fabricating the Seven Ahruf Hadith

Asim had a vested interest in promoting the idea of seven ahruf, especially in Kufa, where his recitation of the Qur’an was highly influential. The Qur’an’s recitation, which Asim played a central role in, could be framed in such a way that it supports his position and influence. The idea of seven ahruf, if fabricated or altered, could have served multiple purposes:

Legitimization of Kufa’s Recitation: Kufa was a center of Qur’anic recitation, and Asim, being a leading reciter in that region, could have emphasized the flexibility of the Qur’an’s revelation (through the seven ahruf) to consolidate his influence over Qur’anic interpretation and recitation.

Altering the Understanding of the Qur’an: By framing the Qur’an’s revelation in seven different modes or ahruf, Asim could have bolstered the argument for regional variations and differences in Qur’anic reading, which were politically significant at the time.

Source: https://x.com/PhDniX/status/1212824936768778245 Archive: https://archive.ph/HEDgT

Source: https://x.com/ShehzadSaleem8/status/1212727235360305153 Archive: https://archive.ph/YS8Ev

However, as Dr. Marijn van Putten, a leading Qur’anic manuscript expert and linguist, highlights, Asim’s recitation within the written manuscript tradition was relatively scarce. While occasional instances of Shubah an Asim can be found, Hafs an Asim — one of the most popular and widespread recitations today — was seldom included in the early written records. This scarcity suggests that Asim’s recitation was not widely adopted or popular in the early manuscript tradition. This discrepancy in the circulation of Asim’s recitation further supports the possibility that the fabrication of the seven ahruf hadith was an attempt to gain greater influence, particularly in Kufa, and elevate his recitation tradition. As a result, the creation and dissemination of the seven ahruf narrative may have been strategically motivated to make Asim’s approach to recitation more authoritative and accepted.

Evidence of Fabrication from the ‘Hasanid Mahdi’ HadithCritic Blog

As mentioned in the Hasanid Mahdi HadithCritic blog, Asim had a history of fabricating or altering hadiths to serve political purposes. That blogpost suggested that Asim was involved in the transmission of a hadith concerning the Mahdi that aligns with Muhammad al-Nafs al-Zakiyya, a political figure who claimed to be the Mahdi during his revolt against the Abbasid Caliphate. This connection between Asim and the Mahdi narrative further supports the argument that Asim had motives for fabricating or modifying hadiths to fit his political interests.

Asim’s Fabrication of the Seven Ahruf Hadith

Given Asim’s tendency to make errors in his hadith transmissions, his central role in the transmission of this specific hadith, the political climate in Kufa at the time, and his potential motivations to promote certain theological or political ideals (such as supporting the idea of a Mahdi from the Alid family), it is reasonable to conclude that Asim fabricated or altered the hadith concerning the seven ahruf. The absence of corroborating chains and the problematic nature of the chain itself suggest that this hadith was not authentically transmitted from earlier sources but was instead a product of Asim’s personal and political circumstances.

The variant readings of the Qurʾān derive their legitimacy from the Prophetic tradition of the sabʿat aḥruf; however, Muslim scholars have had no common understanding of the meaning of the term ḥarf. The mystery of the sabʿat aḥruf has resulted in more than thirty-five different interpretations of this tradition. Nonetheless, despite the vagueness of the concept of ḥarf, the discipline of Qirāʾāt and the meticulous transmission of the variant readings of the Qurʾān were heavily dependent on the mysterious sabʿat aḥruf tradition.

After performing isnād and matn analysis, I conclude that this tradition was in circulation probably by the last quarter of the first Islamic century. This indicates that the multiplicity of the Qurʾānic readings, not long after the codification process by ʿUthmān, still lacked official validation by the Prophet, thus giving way to the promulgation of the sabʿat aḥruf tradition.

The Shīʿīs rejected the accounts of the sabʿat aḥruf and considered this tradition to be one form of the falsification of the Qurʾān (taḥrīf). The integrity of the Qurʾān and the historical accounts pertaining to its collection and codification have been discussed at length in Western scholarship. The dominant theories of the Western scholars range widely from the Qurʾān being the exact final version that Muḥammad left before his death, to the Qurʾān being a document collected and codified no earlier than the third Islamic century.

The Transmission of the Variant Readings of the Qur’an: The problem of Tawatur and The Emergence of Shawadhdh by Dr. Shady Hekmat Nasser (page 34)

Just like the previous narration, when we apply the correct meaning of “أُمِّيَّةٍ” as “gentile nation,” the hadith becomes incoherent. The statement, “I have been sent to a gentile nation, to the old man, the woman, the boy, the girl, and the old man who has never read a book,” no longer makes sense. Being gentile does not inherently imply that a person, young or old, is incapable of reading or writing, nor does it suggest that the entire population lacks literacy. If the seven modes hadith was created to justify Asim’s recitation as well as the existence of multiple variations of the Qur’an, using the term “أُمِّيَّةٍ” with its proper understanding renders the hadith incoherent. How would having seven different modes make the Qur’an easier to understand for gentiles? It would make it easier to understand for illiterates, hence Asim’s misusage of the word “أُمِّيَّةٍ” in his hadith. By incorrectly using the term “أُمِّيَّةٍ” as “illiterate,” the fabricator (Asim) has crafted a narrative that implies illiteracy, which is both historically and linguistically inaccurate when considering the term’s proper context.

Furthermore, the continuation of the hadith—stating that the Qur’an was revealed in seven modes (أُنْزِلَ عَلَى سَبْعَةِ أَحْرُفٍ)—relies heavily on this incorrect understanding. The fabricated link between “illiteracy” and the supposed need for multiple modes (of recitation) collapses when “أُمِّيَّةٍ” is understood correctly as “gentile.” There is no logical connection between being gentile and the Qur’an needing to be revealed in seven modes, making the hadith’s structure fundamentally flawed. This suggests that Asim, the transmitter of this hadith, fabricated it based on a misunderstanding of “أُمِّيَّةٍ” as “illiterate.” Asim appears to have relied on this misinterpretation to construct a narrative that emphasizes the Prophet being sent to an unlettered people and ties this to the supposed revelation of the Qur’an in multiple modes. By doing so, he propagated a false understanding of the term and linked it to a dubious explanation for the concept of the seven ahruf.

QuranTalk provides compelling evidence that the traditional narrative of Prophet Muhammad’s illiteracy is both historically and linguistically flawed. Central to this critique is the analysis of the Prophet’s first revelation. In Bukhari’s account, the Prophet’s response to Gabriel’s command to “read” is recorded as “I am not a reader/reciter” (ما أنا بقارئ). However, this phrasing is ambiguous and does not explicitly indicate illiteracy. Ibn Ishaq, a biographer writing a century earlier, presents a markedly different account. In his version, the Prophet responds with “What shall I read?” (ما أقرأ), a clear indication of hesitation or inquiry rather than an inability to read. Furthermore, Ibn Ishaq’s biography includes multiple instances of the Prophet writing letters and documents, such as the Constitution of Medina and correspondence with leaders, providing strong evidence against the claim of illiteracy.

The term “أُمِّيّ” (ummī), often translated as “illiterate,” is another point of contention. QuranTalk argues that the Qur’anic context defines “أُمِّيّ” as “gentile” or “unscriptured,” not illiterate. This distinction undermines later narratives that sought to amplify the miraculous nature of the Qur’an by portraying the Prophet as unable to read or write. Ibn Ishaq’s omission of any suggestion of illiteracy and his explicit references to the Prophet’s written works strengthen this interpretation.

When applied to the hadith attributed to Asim, this understanding reveals critical flaws. The hadith claims Gabriel described the Prophet’s mission as being to an “illiterate nation” (أُمَّةٍ أُمِّيَّةٍ). If “أُمِّيَّةٍ” is understood as “gentile,” this statement becomes nonsensical in context, as the elderly, women, and children mentioned would not inherently lack literacy due to being gentile. This demonstrates that Asim, like other narrators, misunderstood or deliberately misinterpreted the term. Similarly, Al-Aswad ibn Qays, another narrator, propagated a hadith that conflated “أُمِّيَّةٍ” with “illiterate,” resulting in incoherent conclusions when applied to the Prophet’s nation. Both narrators reflect a pattern of misinterpretation, likely shaped by an agenda to perpetuate the false notion of widespread illiteracy to heighten the Qur’an’s miraculous reception. These fabrications fail to align with the historical and linguistic realities presented in earlier sources.

In contrast, Ibn Ishaq’s account of the Prophet’s compliance with Gabriel’s command to read (فقَرَأتُها) directly contradicts the narrative propagated by Asim. The coherence and consistency in Ibn Ishaq’s biography, coupled with QuranTalk’s analysis, expose Asim’s hadith as a fabricated attempt to align with a misinterpreted theological agenda.

Conclusion & Summary of The Fabricated Traditions –

The correct meaning of “أُمِّيِّين” (Ummiyeen) is “gentiles,” a term that aligns with the historical and linguistic context of the Qur’an. Despite this, the fabricators of the hadith, such as Asim and Al-Aswad ibn Qays, falsely interpreted the term as “illiterates.” This misunderstanding not only reveals their anachronistic misinterpretations but also renders their hadith incoherent when the correct meaning is applied. For example, describing the Prophet’s mission to an “illiterate nation” makes contextual sense, while applying “gentile” results in logical inconsistencies, especially in reference to specific groups such as the elderly, women, and children.

Further supporting this is the absence of any mention of the Prophet being illiterate in Ibn Ishaq’s Sirat Rasul Allah, one of the earliest biographies of the Prophet, as QuranTalk mentioned. Instead, Ibn Ishaq records instances where the Prophet wrote letters, undermining the narrative of his illiteracy. The earliest mention of the Prophet in connection to illiteracy appears in Asim’s hadith on the seven modes (ahruf), which, when dated, identifies Asim as the originator of this Hadith.

This timeline and the incoherence of the hadith when applying the correct understanding of “gentile” strongly indicate that the notion of the Prophet’s illiteracy was a later fabrication designed to magnify the miraculous nature of the Qur’an’s revelation. By tracing the hadith to their fabricators, it becomes evident that this claim lacks both historical and linguistic credibility. Based on the research conducted thus far, it seems the earliest account of the Prophet Muhammad having anything to do with illiteracy comes from the hadith of Asim. Instead of it being understood to the Prophet, the term is being applied to his people (أُمِّيِّين).

Asim- The goal of his hadith is to push the idea that the prophet’s nation was ‘illiterate’, which would justify the idea of the Quran being recited in several modes. This hadith is the earliest of the ones that claim *his people* are illiterate, but not himself.

Ibn Ishaq- The Sirah of Ibn Ishaq actually provides evidence that the prophet knew how to read and write as pointed out by QuranTalk. It contains 0 instances of the prophet being illiterate.

Al-Aswad- Within the same year as the Sirah, Al-Aswad has his narration: “We are an unlettered nation; we do not calculate or write. The month is like this, and like this, and like this,” and he (the Prophet) folded his thumb on the third time (indicating 29 days). His narration more clearly emphasis both the prophet and his nation being illiterate, which would mean the earliest account of the prophet being ‘illiterate’ is with Al-Aswad.

It is worth noting that both Asim and Al-Aswad, despite not appearing together in isnads or sharing the same hadith, were narrators from Kufa. Given this connection, it is reasonable to conclude that the notion of the Prophet being illiterate or sent to an illiterate nation likely originated in Kufa, based on these observations.

Al Aswad Hadith: “We are an (Ummiyeen) nation; we do not calculate or write. The month is like this, and like this, and like this,” and he (the Prophet) folded his thumb on the third time (indicating 29 days). [He understood it as illiterate – applies it to Muhammad + Nation]

Asim Hadith: The Messenger of Allah met Jibril and the Messenger of Allah said to him, “I have been sent to an (Ummiyeen), among them are the youth, the maid, the elderly woman, and the elderly man.” Jibril said, “Command them to read the Qur’an in seven dialects.” [He understood it as illiterate – applies it to Nation]

Last updated